On Friday, the U.S. House will take the rare step of holding a vote on statehood for Washington, DC. The “Washington, D.C. Admission Act” (H.R. 51) would maintain an existing capital district that encompasses the spread of federal buildings in the city’s core. The remainder of the current district would gain admission as the nation’s 51st state, offering voting representation in the House and Senate to its more than 700,000 residents.

Understanding the history and impact of this move is important.

Has Congress tried this before?

Members of Congress have filed D.C. statehood bills for decades—a move most frequently from D.C.’s non-voting delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton. In 1993, Congress voted legislation out of committee and it went to the House floor for a vote. Also, numbered H.R. 51, The 1993 legislation was titled the “New Columbia Admission Act.” It failed badly before the whole House by a vote of 153-277. The House has not voted on D.C. statehood since, and the Senate never has.

Who voted for the 1993 D.C. statehood bill?

The breakdown of the vote on the 1993 bill shows some interesting divides. The current bill has robust, nearly universal support from House Democrats. However, that Democratic lockstep approach to statehood was not true 27 years ago. Democrats split their votes on the 1993 legislation with 151 voting in favor but 105 voting against. One Republican, Wayne Gilchrest, who represented parts of northeastern Maryland and the state’s Eastern Shore, voted in favor, as did the House’s only independent, Bernie Sanders (Vt.).

The two states that surround D.C.—Virginia and Maryland—had 11 and 8 House members, respectively (as they currently do, as well). Virginia’s entire delegation voted against the bill with the exception of Democrat Bobby Scott (3rd District). (Rep. Scott still holds that seat today. Maryland’s delegation was split 4-4, however not evenly across party lines. Republican Rep. Gilchrest voted in favor, while Democratic Rep. Steny Hoyer (5th District) and now House Majority Leader voted against the bill.

Overall, there are 36 House members who voted on the 1993 bill who are still serving in the House today. They include 7 Republicans and 29 Democrats. Of those members, all seven Republicans voted against, and 24 of the 29 Democrats voted in favor. The five Democrats voting against tended to be moderate, white Democrats: Steny Hoyer (Md.), Marcy Kaptur (Ohio), David Price (N.C.), Collin Peterson (Minn.), and Jim Cooper (Tenn.).

With the exception of Leader Hoyer, the other key figures in Democratic House and Senate leadership were serving in the House in 1993 and voted in favor of the bill: Rep. Nancy Pelosi (Calif., now Speaker of the House), Rep. Jim Clyburn (S.C., now House Majority Whip), Rep. Chuck Schumer (N.Y., now Senate Minority Leader), and Rep. Dick Durbin (Ill., now Senate Minority Whip).

Who supports the 2020 D.C. statehood bill?

The legislation is sponsored by Del. Norton (D.C.) and has 225 cosponsors (including non-voting delegates from places like Guam. Of the voting representatives in the Democratic Caucus, 11 are not included as cosponsors. They include Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, although it is customary for the House speaker not to cosponsor legislation. Given her support of the 1993 bill and willingness to have a vote scheduled, it is certain she is supportive. Of the remaining 10, one member Pete Visclosky (Ind.) voted in favor of the 1993 bill. Of those remaining nine, two members, Jim Cooper (Tenn.) and Collin Peterson (Minn.) opposed the 1993 legislation.

This leaves seven Democratic members who have no voting history from 1993 and have not signed on to cosponsor the 2020 bill. They are Anthony Brindisi (N.Y.), Joe Cunningham (S.C.), Jared Golden (Maine), Kendra Horn (Okla.), Tom O’Halleran (Ariz.), Elissa Slotkin (Mich.), and Xochitl Torres Small (N.M.). Each is a moderate member. All except Rep. Slotkin belong to the Blue Dog Coalition, and each hails from a Republican-leaning congressional district. For context, the average Cook PVI score, among the districts represented by those seven members is R+5.7.

The delegations of Maryland and Virginia have also changed dramatically. With all Democrats in both states (seven in Maryland, including Steny Hoyer, and six in Virginia) supporting the legislation, while all of Maryland’s and Virginia’s Republicans (five in total) oppose the bill.

In fact, there are no Republicans cosponsoring the legislation. Rep. Jeff Van Drew (N.J.) was an initial cosponsor on the legislation. However, after switching his affiliation from Democrat to Republican, he withdrew his co-sponsorship of the bill.

What would the statehood bill do in effect?

The legislation would most obviously add the 51st state to the U.S., which under the legislation would change “District of Columbia” to “Douglass Commonwealth,” maintaining the “D.C.” abbreviation, while paying homage to Frederick Douglass. It would grant voting representation to the residents of D.C., adding one member to the House and two Senators. The House would grow by one member to 436, then after the next census return to 435 apportioned among the now 51 states.

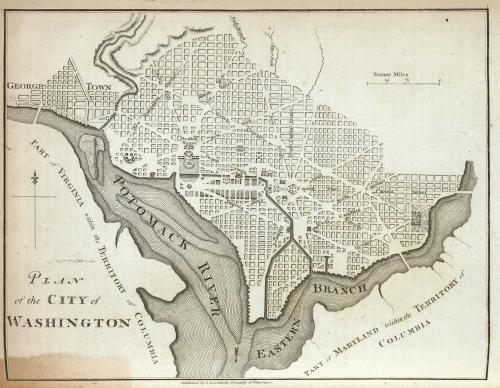

The bill carves out specific space for a capital district to remain, largely encompassing the clustered government buildings surrounding the national mall, and including the White House and other areas, over which the federal government would retain complete control. It would transition the D.C. Mayor to the title of “governor” and the district council would function as the legislative body. D.C . would be granted all of the rights of any state, while the current district’s Home Rule policies, mandated by Congress would be dissolved.

It would also work to repeal the 23rd Amendment (granting D.C. electoral votes in presidential elections), as it will be moot and the existing capital district would have few if any people residing in it.

The politics of D.C. statehood

Republican opposition to D.C. statehood rests in large part on politics. Given the overwhelming Democratic voting in Washington, it would be unlikely that Republicans would elect a House member or senator from D.C. As a metric, since 2000, the Democratic presidential nominee captured, on average, over 89% of the vote.

President Trump has vowed to veto DC statehood legislation; however, it has no chance of passing the Senate as Majority Leader McConnell has criticized the legislation. In addition, in vilifying the effort, President Trump has rightly noted that Democrats would likely pick up two additional Senate seats. However, he wrongly noted that Democrats would add five additional House members.

D.C’s population sits at just over 700,000 people—more than Vermont or Wyoming and slightly less than that of Alaska. That population would entitle it to one House member. In order to pick up a second House seat, D.C. would likely have to increase its population by about 50%. Given the size and population density of D.C. (more than 10,000 people per square mile) as well as limits on the height of structures in the city, that figure is effectively unreachable. To have five House members—as do Connecticut, Oklahoma and Oregon—D.C. would have to more than quintuple its population.

And yes, while the addition of a near certain Democratic congressional delegation presents a political gift that is hard for Democrats to pass up, there are other factors at play in the debate. D.C. residents pay taxes, but have little influence on how taxpayer dollars are allocated. D.C.’s delegate must rely on committee influence (but only when she is allowed it) and the support of other voting members to assist her constituents. This is a situation that most famously created the D.C. license plate slogan “Taxation without Representation.”

Moreover, D.C. is governed by Home Rule, which allows Congress to invalidate any law or initiative the D.C. government or its voters pass. In addition, Congress can use the appropriations power to affect the manner in which D.C. is run. It is also a majority-minority city with only 37.5% of residents identifying as white non-Hispanic. And given the current policy environment, the disenfranchisement of more than 400,000 Black and Latino voices has a negative impact on the policymaking conversation, particularly on issues that are so meaningful to those communities.

Ultimately, H.R. 51 will pass the House and fail to come to a vote in the Senate. Even if the Senate were to pass the legislation, a presidential veto awaits it. However, the serious step of passing statehood in the House likely foretells what will be a major legislative priority in some future period when Democrats control the House, Senate and the presidency.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Commentary

The politics and history of the D.C. statehood vote

June 25, 2020